I hate giving feedback. I’m scared to do it wrong. I’m scared to be wrong. I am not qualified for this.

Emma: Of course you’re qualified. If you can see a problem, that means you’re qualified to provide feedback.

Andy: If you can see it, you can say it!

Emma: If I’m not able to articulate it, I’m still qualified — I’m just not ready. That was a huge distinction for me.

You don’t need to instantly know what’s wrong.

Three things help me get ready. First is getting over any insecurity of not knowing right away why something is wrong.

I need time to put language to it. I’ve decided it is better to be a boss who gives useful feedback a few hours later than a boss who gives aimless feedback on the spot.

Andy: Yes! You can just say, “Let me think about this for a few hours.” Or have your report send you something in the morning, and wait until the afternoon to share your thoughts. A few hours later is totally timely.

Emma: Scorecards are a really useful tool during those hours. When the work is wrong, it’s not going to line up with something we’ve written down as an expectation. A scorecard is basically a feedback crib sheet. But I also like asking for help.

Help isn’t cheating.

I take things to my boss: “Hey, I know something is wrong with this. Can you help me articulate it?” Or I Slack a co-manager: “What’s weird about this?” Or I ask someone on the team whose work I love: “What do you see?” This isn’t cheating. This isn’t a sign I’m not worthy of my title. It’s proof that I want to provide the best feedback I can to someone who is struggling.

Isn’t that a cool shift in perspective? It’s not about me! It’s about the people on my team who can be better. And that’s why we say giving feedback — critical, helpful, articulate feedback — is an act of generosity.

Andy: Realizing it’s generous to give honest feedback was the biggest brain shift I’ve ever had. When I tell someone something honest that’s not all stars and praise, I am not the Grim Reaper. I don’t need to go in wearing a don’t-kill-the-messenger t-shirt. I don’t even need to feel like a bearer of bad news. I’m simply a person with useful information. Soon, the person getting feedback will be better and their work will be better, maybe for the rest of their life. How can I put that off another six weeks or six months? How can I steal that time from them?

However, even after I realized feedback was generous and good and I wanted to give it, I still caught myself questioning, “What if I’m not qualified? What if I’m wrong about this stuff?” This was especially true when the person getting the feedback was more experienced, or smarter, or went to a better college, or clerked for Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Emma: Oh yes, giving feedback takes a little bit of bravery, too. You are putting your thought process on display. You have to defend your point of view. Someone could even disagree. That felt like a lot to take on as a new manager.

I think the need for a little bit of bravery is why unhelpful feedback is so pervasive. One of my best friends is a copywriter. Her boss will often just write WC at the top of the page, which means word choice. My friend gets two letters of feedback. Where’s the bravery in that?

Andy: There’s literally none. It’s making her put her forehead on a bat, spin around 10 times, and try to find a better word. And then she has to muster the bravery to plate up a new word for approval.

Emma: That little bit of bravery is also why we so often just fix bad work ourselves. Or give the work to someone else. Or cancel the project, or hope that no work like this ever comes up again and we can all just ignore there was ever a problem in the first place.

Feedback is unavoidable.

Andy: Unfortunately, without feedback the problem stays and it gets worse. It’s workplace athlete’s foot.

Emma: When I need to rally my wits to give someone feedback, I try to flash-forward to my next job interview. The interviewer will inevitably ask me about a time I had to give feedback. I imagine plumbing the well of my experience and finding all I have to say is, “Oh, I usually ended up just fixing the work myself.” And then I imagine not getting the job.

I want to have an arsenal of success stories. I want to be able to talk about how the people who struggled on my team grew like crazy. And that helps give me the mental wherewithal I need.

5 Rules for Good Feedback

1. Frequent feedback makes it not a big deal. Routine weekly feedback diffuses that feeling of THIS IS A BIG BAD FEEDBACK MOMENT and gives you the freedom to give even micro feedbacks. Plus, you won’t have a huge stockpile of stuff to plow through, say, once a quarter, or the embarrassment on both sides that a problem has been going on for so long.

2. You don’t need to have the solution. Think about it like this: If you don’t like your boyfriend’s chocolate chip cookies, it’s not particularly helpful to just say, “I don’t like these cookies.” But you also don’t have to say, “You need to cook them at a lower temperature and use more butter and try this other pan.” Good feedback is, “I think they should be doughier in the middle.” Then, your boyfriend is able to go research how to make doughier cookies. Or he can ask you if you have any tips, or if he can call your grandma who makes the perfect chewy cookie. The feedback part is over pretty fast. Now you’re just working together to solve a problem.

3. Acknowledge the situation the work came out of. Were your instructions bad? Was the project last minute? Is it something new they’ve never done before? Clear the air first, then dive into what’s not great.

4. Don’t sandwich. Do use examples of good work. “Love your hair. Hate that dress. You look so beautiful.” Sandwiching seems like it’ll soften the blow and give you a nice, gentle exit. In actuality, it’s confusing and weird. Keep compliments topical by pulling out examples of great work that don’t have the problem you’re talking about, and praising your report for that.

5. Don’t panic if there’s pushback. Our tip: Accept any challenges with enthusiasm and appreciation — even a corny-seeming phrase like, “I love that question.” If you know the answer, you can follow it with, “Let’s dig in more.” If you have no clue, buy yourself some time: “Let’s set up a time tomorrow afternoon to come back to it.” Remember, you own the tone of this encounter.

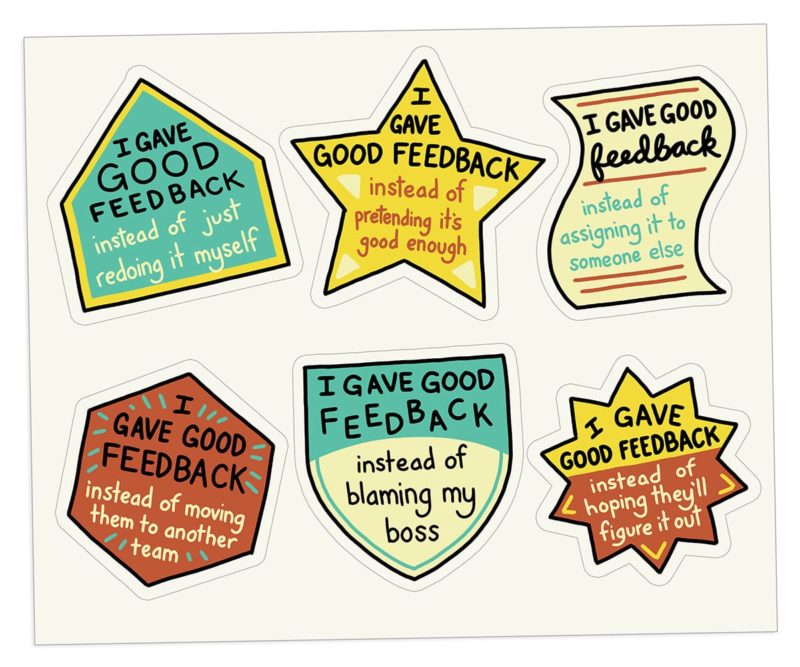

Good Boss Achievement Stickers: Feedback Edition