Emma: I can tell you what it feels like to fail. It sucks. It feels unfair. You can feel it in your body. I feel failure in my chest the most. It literally takes my breath away.

Failure is an absolute certainty when you’re a manager. The big, visible, high-stakes, stomach-dropping kind. It’s too hard a thing to not fail at. I don’t think we acknowledge that enough. Instead we spend a lot of time feeling shitty for failing, or dreading that we’re about to fail, or trying to ignore the failures that are beginning to stack up.

Most new managers aren’t used to being bad at things. As a former new manager, I can say this with a certain degree of authority. It makes sense. We tend to be high performers. We work hard and collect praise. We’re usually among the best of our peers at the thing we’re about to be managing, and we avoid the stuff we aren’t good at.

Suddenly we’re managers and everything we’re trying to do is brand new, we don’t have much help, and we do a bad job. I hadn’t been so blindsided by something — or as indignant or as self conscious — since my sophomore year in college, when I got a D (a D!?!!) on my first literary theory paper. Feeling like I was bad at my job that much, that often, and where so many people could see me, was wrenching.

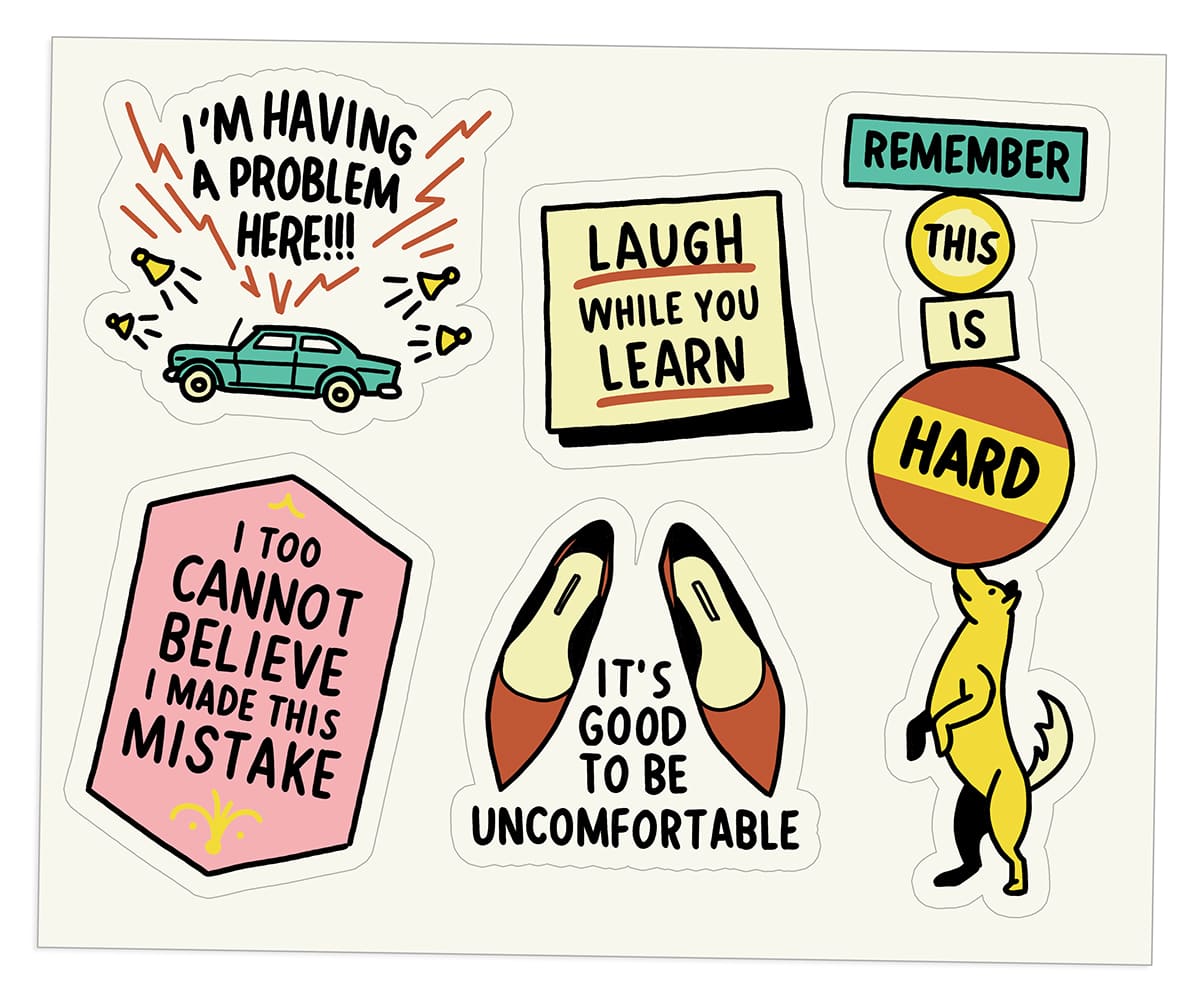

You know how people always say, “It’s good to be uncomfortable”? I’m pretty sure that wrenching feeling is what they are referring to. And I did not know that. I associate discomfort with pointy-toed shoes, not psychic dread.

When I started managing, I hadn’t learned how to articulate what success was, and couldn’t identify what I was working toward — just some hazy concept of a Good Boss floating beyond my reach. And that created a kind of existential perma-dread: I always felt like I was failing, or on the verge of failing, even though I never had a good answer when someone asked me what I was so scared of failing at.

In some of those moments Andy used to ask me, “What are you afraid of?” And I would have to name them. Always, without fail, it would take me a few tries. Because I didn’t really know.

When I eventually could identify my fears, I’d start to snap out of it. Because they either gave me something specific to do — ask for help, do some research, make a plan, practice — or because they sounded completely absurd when spoken aloud. (No, I wasn’t going to get fired for flubbing one question in a meeting.) Answering that question was like performing an exorcism.

I do this all the time with my direct reports, too. As a manager, it’s really hard for me to assuage a general malaise. The more specifics I get, the more effective I can be in helping solve it. What are you afraid of? Write it down. Speak its name.

I have a goal as a manager: to have grace and good humor even if I am fucking something up. I put a sticky note on my computer for years that said laugh while you learn. That sticky was a hack to help me get there, the instructions to a trick I played on myself whenever I was floundering in my failure. I would tell myself, “This is just learning!” And then I would literally make myself laugh out loud: “Ha ha ha!”

Two Simple Questions to Cut Through Your Fear of Failure

Fear of failure is a wily beast. It can grow to almost any size and outwit airtight logic. When you’re feeling dread, get out a piece of paper, fold it in half, and write these two questions on it:

- What do you want?

- What are you afraid of?

Dump your entire mind out – everything you want in the situation, and every fear you can conjure up. On paper the fears are like invisible ink: They’re not so scary, they’re often totally absurd, and they’re solvable. (It works even better if you do this with a friend. Literally hand them the paper and ask them to ask you the questions.)

Andy: Back in May, I served as an election inspector, a volunteer position I’ve wanted (and have been waitlisted for) for three years. I sat at a table for 16 hours and was in charge of making sure ballots were legally cast and — guess what? — I made mistakes.

Andy: Back in May, I served as an election inspector, a volunteer position I’ve wanted (and have been waitlisted for) for three years. I sat at a table for 16 hours and was in charge of making sure ballots were legally cast and — guess what? — I made mistakes.

I accidentally accepted a ballot that should have been cast across the room; I dropped a provisional ballot into the locked box of the other ballots, never to be distinguished again; my ballot count didn’t match my signature count, so however many cast ballots I had in my official red ballot box wasn’t right. It didn’t feel good. I was tired and imperfect, and still needed to pack the polling station into the trunk of my car and drive my imperfect ballot box to the drop-off center. I thought, “I’m almost done. I’m almost off for the night.”

When I was packing my supplies into my car, a man called after me, “You dropped a ballot.” I thought he was playing a practical joke. I literally said, “Ha.” But he wasn’t joking. He was waving a real ballot, one that’d fallen out of my ballot machine as I dragged it across the parking lot.

Oof.

What came next? I drove to the ballot drop-off location to hand over my sealed box and one stray ballot and told an angry man in a fluorescent safety vest that I messed up. There was a lot of muttering, and a very loud, very annoyed, “I cannot believe this!”

This is a lot of what managing felt like to me at first: I was new, it was hard, there was a lot to remember, and just when I thought I’d made as many mistakes in a single day that I possibly could, another one — an even bigger one — jumped up and bashed me in the face.

Every micron of my being doesn’t want to fail. It wants to be great and perfect and the best at it all. That night, when the safety-vest man said he couldn’t believe my mistake, I wanted to say, “Me either! I too cannot believe I made this mistake.”

But another, softer part of me said, “Of course you made a mistake. You are human. This is hard. You are tired and hungry.”

How’d my failure end? Not with a giant parade of how dumb I was, literally the worst inspector in all the state. I just had to take the end of a pen and break the seal on the ballot box (in the presence of a witness and a sheriff, but fine), put the ballot back in, reseal it with some blue painter’s tape, and sign my name to my mistake. Then I got to drive home and go to sleep.

My favorite Car Talk episode is the one where someone calls in and asks what to do when they stall their stick-shift car. (I can’t find it in the archives. Can you? Let me know!) The cars around them get exasperated and angry and start honking. The honking makes the driver more nervous, and they forget what little they know about operating a stick-shift.

Click and Clack laughed and empathized because who in a stick-shift hasn’t been in that situation? And then they suggested rolling down the window and shouting, “I’m having a problem here!” It’s such a funny image to me, and so honest. It reminds me that the rest of humanity has room for my mistakes if I will too.

Good Boss Achievement Stickers: Failure Edition

Celebrate your victories with our weekly set of Good Boss Achievement stickers.