Andy: This week I’ve been thinking a lot about how to listen to a problem and really hear it — and not jump in with a solution.

Emma: A truly worthy endeavor. How’s it going?

Andy: Okay? It’s not my natural state. I am fast to interpret a sentence as a task, as something I can solve. I like to reassure and make promises, and as a manager, it’s easy to fall into the belief that it’s my job to deliver on those promises. You don’t want to change desks for the twelfth time? Gotcha. Watch me spring to action!

Emma: I think one of the most complicated parts of being a manager — especially a low- or mid-level one, which is where many of us spend our time — is that we don’t actually have a lot of power. It’s hard to really do anything that’s not just what we are told to do from on high. Realizing this was one of the first times I ever really felt like a failure as a boss.

Andy: Right? Cut to: me back at my desk, asking the person in charge of the seating chart what we could do about my team member who doesn’t want to move her desk. Nothing, is what we could do. The machine was already in motion, and stopping it to accommodate one person’s complaint wasn’t worth the ripple effect.

As a person I felt crappy — False Promise McGee over here! — and as a manager I felt even worse. Not moving desks was a small-enough ask, and in all other realms of my life, I could effect change on that level. Now I felt small on top of feeling like a liar.

Emma: We hear about the best managers being fierce and crafty and unstoppable, intrepid salmons swimming upstream against the status quo to champion Big Sweeping Changes.

Andy: How do salmon do it? How could humans ever do it!?

Emma: So often we’re kind of trapped: on one side is our team, telling us that they’re unhappy, or that there’s a problem, or that something isn’t fair; and on the other is an entire institution that keeps on chugging along. There’s just not a lot of wiggle room in that space, which is why a lot of the time we wish the people on our teams could simply STOP COMPLAINING.

Andy: Empty guarantees are an easy way to get that result — at least temporarily. “Sure, I’ll get right on that…”

Emma: Or you can shut it down: “Instead of problems, why don’t you bring me solutions?”

Andy: That’s about as welcoming a manager move as a shark enclosure is to a penguin. And some things are worthy of complaints and swift action and tenacious problem solving: harassment, illegal activity, health concerns, any HR violation. We need our team to raise these complaints and we need to solve them.

But on the day-to-day, I’ve really had to learn how to hear something without promising to fix it, which is frustrating if only because it’s the opposite skill that’s required of getting to management level. It felt like starting from scratch again.

Emma: When I’m feeling especially trapped, or I’m being overwhelmed by complaints from an unhappy team, or someone I don’t like very much is voicing yet another concern, listening well becomes a hyper-intentional practice: I know it’s not necessarily going to come naturally, so I’m going to have to really focus and go through the steps. One of the ways that works for me is to make it into a game called What Do They Really Want?

Sometimes, yes, it’s right there on the surface and you can take it at face value: I would like a raise because I’ve been increasing my responsibilities and doing excellent work that I should be compensated for. But often, there’s something deeper going on, and I make it my mission to ask enough questions to figure it out. Are you really mad that you’re moving desks again? Why? What impact does it have on you? Unless you have some sort of physical ailment, it’s not the actual moving part. Are you dreading sitting next to someone I didn’t know you have beef with? Feeling like your tenure means you should get a window seat? Behind enough in your work that the 30 minutes of packing then unpacking means you won’t hit your deadline? Help me understand so we’re both talking about the same thing.

Andy: I’ve found that this sort of external processing is often what a person is looking for: the freedom and some help figuring out what is actually rubbing them the wrong way, making them feel sad or bad, frustrating them so much they feel like they’re going to pop. Ann Friedman referenced a probably-Chekov quote in her newsletter this week: “The job of the writer is not to solve the problem, but to state the problem correctly.” Same applies for managers.

Emma: Plus, uncovering the real problem is the first step if you are going to end up solving it. It’s a good one to start with no matter what.

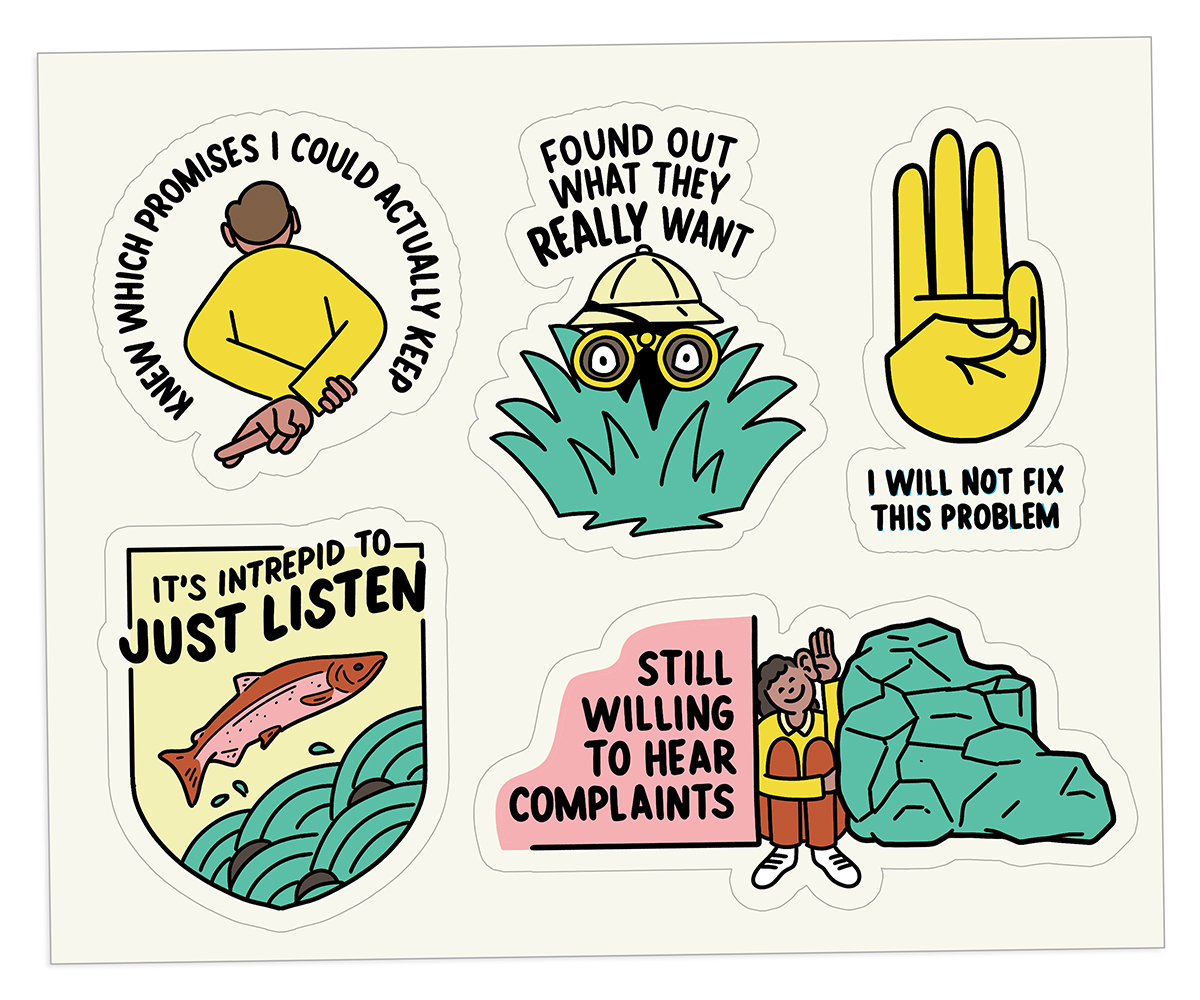

Good Boss Achievement Stickers: Email Ask Edition