Where do I draw the line between wanting to nudge my employees to grow and learn more, and also acknowledging their limitations? What if someone on my team is not inclined to grow the way I would like them to grow?

Andy: Part of the answer to this question, especially coming out of last week’s conversation about millennial burnout, is to, real quick, take stock of why you want to nudge your employee to grow and learn more. Do you know why?

Emma: Do they?

Andy: Some people strive for growth at their job purely for the sake of growth. For more. Because for better or for worse, they are programmed that way. Those types of high achievers are often pretty easy to manage, particularly if the place you work has a lot of room for them to advance, or a lot of money to reward them with, or both. It’s like teaching A+ students: you just point them in the right direction and get out of their way.

Emma: Right. And if that’s what you’re used to — or you are yourself — B-students are bewildering. They have so much potential! If they just worked a little bit harder, they could get straight As too!

Andy: That rationale doesn’t work with high schoolers and it doesn’t work with the employees I imagine you’re writing about. Which brings us back to: Why do they need to learn and grow?

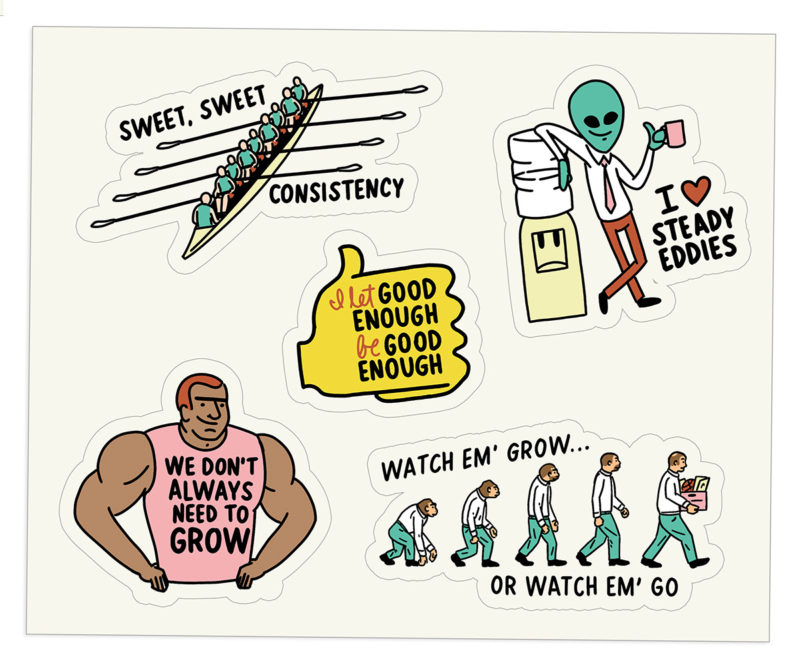

If your only answer is, “Because I want them to reach their potential,” or, “They could be doing more,” I think you might have what we call a Steady Eddie on your hands.

Emma: And with that, The Bent is officially a hotel conference room Leadership Seminar! You’ve got your Steady Eddies, your High-Achieving Hannahs, your Room-for-Improvement Rudys.

Andy: We’ve got DVDs for sale in the lobby!

Emma: A Steady Eddie is someone who is good at their core job.

That’s it.

Andy: In our performative workaholism world, Steady Eddies can look like underperformers and like dead weight. They show up, do the job you ask them to do, then go home. They’re not putting in a lot of overtime. They aren’t surfacing and solving big problems, and they aren’t setting stretch goals. They might not be communicating any goals at all.

Who is this alien and what are they doing on your team?

Emma: They are producing consistent, solid work, that’s what. Emphasis on consistent. If everyone on your team is always trying to level up, you’re always having to find places for them to level up to, even if that means off your team.

And that’s great. It’s a Good Boss thing to do to help get your people where they want to go. But the equal and opposite reaction of that Good Boss behavior is that you’re constantly having to backfill — and it’s hard to keep the boat moving at speed when you’re losing rowers.

You want a great crew of Steady Eddies. You need them.

Andy: None of this is to say that a Steady Eddie shouldn’t grow at all. No team has room for a person who refuses to hear the feedback they’re given, or is too rigid to adapt to tweaks to their job description. And I’ve had very technically competent people on my team who were also very vocal about how much they hated the work or the company or the role. These are not the Steady Eddies you need. These people actually are dead weight. They either need to grow up or grow out.

Emma: You can respect Steady Eddies by allowing them to do a good job and nothing more. I’ll argue that it’s still respectful of their limits to require them to do a good job at the entire job they are supposed to be doing. If they cannot, then it’s not the job they should be doing. And they need to go.

My advice is to get really specific in your feedback. Attach a timeline to the outcome you need, and consequences if they don’t achieve that outcome. Work closely with your person during this time. Watch them grow, or watch them go.

The 5 Stages of Feedback

1. Knowing the precise feedback you need to give. Being able to articulate feedback isn’t easy. It often involves building a scorecard, sifting through work samples, sourcing other perspectives, and acknowledging where you’ve been part of the problem.The first feedback you give may be to yourself: I didn’t set this person up for success. I am going to own that and try something different next time.

2. Setting clear expectations. If it’s the first time you’re sharing these expectations, keep the conversation light. This isn’t a corrective behavior talk. It’s about getting on the same page.

3. Working to hit expectations. Now comes the corrective feedback. Provide it promptly and regularly, and attach it to the expectations from Stage 2. Recap any in-person conversations over email — it’s pretty common for people to kind of blackout when they’re on the receiving end of feedback, and it’s nice for them to have something to look at later. (This also does double-duty as documentation. If performance doesn’t improve, you’ll have clearly documented your efforts and feedback over time. We typically loop in a boss and HR at this stage as well.)

4. Performance Improvement Plan. If performance still isn’t improving, it’s time for a PIP. Definitely check in with HR if you haven’t already. They’ll probably have a process and steps you’ll need to take. On the off chance you’re flying solo, though: A performance improvement plan is a formal outline of the progress that needs to be made and what will happen if those benchmarks aren’t hit — typically termination or reassignment. Be extremely clear, support the improvement, keep giving honest and prompt feedback, and follow through all the way.

5. Graduating from a PIP. Being on a PIP shouldn’t leave a permanent scar. Past performance does not indicate future potential. Let yourself be impressed by their willingness to be coached, their commitment to applying feedback, and the hard work you’ve both done. Celebrate it. Then, go back to Stages 1 and 2 and make sure you’re continuing to do your part in articulating feedback and setting clear expectations.

Good Boss Achievement Stickers: Steady Eddie Edition